The NBA's 3-point Variance Lie

Does shooting more 3's increase your variance?

Let’s double click into that.1

Note, this has been a draft in my newsletter since 2022. Finally publishing it.

Simulations

We ran some very simple simulations. The simulations over-simplify the game of basketball, but that’s the point. The people who make claims about three point shots increasing variance in basketball would accept the terms of these simulations.

Here’s the details of our simulations:

Each team gets to make 100 shots a game

Each team can decide how they want to distribute the shots (number of 3PT shots, number of 2PT shots)

2PT shots and 3PT shots have the same expected value

Number of made shots (and therefore, final score) is drawn from a binomial distribution

That’s it. Like we said, this is a very unrealistic view of basketball. But, the variance-believers essentially use those assumptions when they make claims like this:

While a triple-heavy attack is, in game theory parlance, a dominant strategy, it’s also a high-variance one. 3s are worth more than other shots and they go in less frequently, reducing the predictability of individual games. - hoop76.com from 7 years ago.

Here, we start by comparing two teams: 1 team takes all 2PT shots, and the other team takes all 3PT shots. Since 2PT shots and 3PT shots have the same expected value, both teams are scoring about 100 points on average. But look at the variance. The 3 point shooting teams have a higher probability of going off for >120 points in a game. This is exactly in line with what the variance-believers are talking about!

But teams aren’t shooting all 3’s or all 2’s. The problem arises when we start looking at more realistic looking numbers. Here we’re comparing a team that takes 20% of their shots from 3 to a team that takes 40% of their shots from 3. You can already see the myth falling apart. The team that takes double the amount of shots from 3 hardly has a heavier tail.

But let’s look at it from a strategic point of view. If you are a worse team, should you take more 3PT shots to increase your variance and increase your chance of beating a better team?

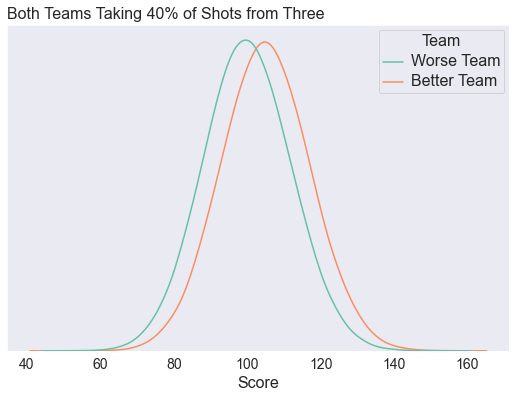

Here’s two teams that take the same number of threes, but one team is better than the other team by 5 points on average.

In the plot above, you can see that the worse team can beat the better team due to chance, even without increasing their variance by shooting more threes. But what if the worse team tries to increase their variance by taking more threes? For the worse team, we’ve simulated games where they take between 20% of their shot from 3 and 60% of their shots from 3. And then for each volume of 3PT shoots, we look at the probability they beat the better team

As expected, taking more 3s increases the chance that the worse team can beat the better team! But look closely at the y-axis. Increasing your 3PT shooting from 20% of shots to 60% of shots only increases your probability of winning from 36.7% to 37.5%. Again, the point is that once you use realistic numbers, the effect size is hardly noticeable.

So what’s really going on here?

Where did this myth come from? I think there’s at least two plausible explanations:

There’s a ton of variance in basketball. When people get exposed to the variance, they naturally want to attribute it to things. And since statistically its true that 3PT shooting increases variance (even if it hardly explains the variance they’re seeing), it’s an easy target.

3PT shooting increases variance in ways not captured by our simulations. But the point is that 3PT shooting doesn’t materially increase variance simply due to it being a lower probability shot worth more points.

Our money is on the second one.

Looking ahead

I’ve been meaning to iterate on our stat prediction model by using a negative-binomial model to have more control over the variance. I’m looking forward to those results.

A few weeks ago I got a job offer at a company where multiple people during the interview process used the phrase “double click”. I’m not saying it was the main reason I turned down the job offer, but it was in the top 3.

Good stuff. I believe the idea has always been that the underdog should take more 3s because expected value otherwise is worse than the favorite. Your assumption that expected value is the same between 2s and 3s makes this a moot point. Perhaps do a simulation where expected value for one side is lower than the other and see if they win more often by increasing the rate of 3s. Or maybe I should get off my lazy ass and do it lol.

Great analysis.